- Home

- Rory Clements

Corpus

Corpus Read online

Praise for Rory Clements’ acclaimed John Shakespeare series

‘Does for Elizabeth's reign what CJ Sansom does for Henry VIII's’

Sunday Times

‘An exuberant plot that hums with Elizabethan slang, profanity and wit ... a bawdy, engaging romp of a book’

The Times

‘Enjoyable, bloody and brutish’

Guardian

‘An engrossing thriller’

Washington Post

‘A world spiced with delicious characters . . . The novel wears its historical learning lightly, and Clements seasons it with romance and humour’

Mail on Sunday

‘An historical thriller to send a shiver down your spine … atmospheric … the evocation of the filth and debauchery of London is quite exceptional … demonstrates the compelling eye for detail and character that Bernard Cornwell so memorably brought to Rifleman Sharpe. I could not tear myself away, it is that good.'’

Daily Mail

‘Clements has the edge when it comes to creating a lively, fast-moving plot’

Sunday Times

‘Faster moving than CJ Sansom’

BBC Radio 4

‘A colourful history lesson [with] exciting narrative twists’

Sunday Telegraph

'Beautifully done . . . alive and tremendously engrossing'

Daily Telegraph

'Sharp and challenging, this book is missed at one's peril'

Oxford Times

'A cracking plot full of twists right up to the last minute’

Sunday Express

‘Raises Clements to the top rank of historical thriller writers ... an intricate web of plots and subplots vividly evoking the tenor of the times’

Publishers' Weekly

‘A cornucopia of elements to praise here, not least the vivid and idiomatic historical detail ... The plotting is adroit, and continues to surprise the reader at every turn. John Shakespeare is one of the great historical sleuths…’

Barry Forshaw

‘What most impressed me was Clements' ability to set a fast-paced crime thriller in the London of 1593 and to make it entirely convincing…’

Edinburgh Book Review

‘A delicious feast of fact and fiction, adventure and adversity…’

Lancashire Evening Post

RORY

CLEMENTS

CORPUS

Contents

Berlin, August 1936

Chapter 1

England, Monday November 30, 1936

Chapter 2

Tuesday December 1, 1936

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Wednesday December 2, 1936

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Thursday December 3, 1936

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Friday December 4, 1936

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Saturday December 5, 1936

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Sunday December 6, 1936

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Monday December 7, 1936

Chapter 41

Aftermath

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

A message from author

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

For Naomi

BERLIN, AUGUST 1936

CHAPTER 1

The man was grey-haired, about fifty, and carried a black briefcase. He wore black trousers, a brown linen jacket, white shirt and striped tie but no hat. He might have been an office worker, except for the white socks and brown, open-toed sandals. White socks and sandals. In the middle of a working day, in the traffic-mad tumult of Potsdamer Platz, in the centre of Berlin. He was standing beside her at the edge of the pavement, waiting to cross.

Nancy Hereward turned her head and caught his eye. She stared at him hard and he looked away. She felt like laughing, but her mouth was dry and she had a terrible thirst. Surely, if he was following her, he wouldn’t have made eye contact? Nor would he have dressed so distinctively. If you were tailing someone, you had to meld into the crowd, not stick out. A gap opened up between the trams, the buses, the cars and the horse-drawn carts, and he made a dash for the other side of the road by way of the clock tower island. Nancy waited.

Ahead of her, a policeman with white gloves was directing the onrush of vehicles. To her left, two young women in sunglasses were examining postcards at a newspaper kiosk. They wore flat slip-on shoes and short-sleeved, calf-length summer dresses, one polka-dot, the other floral, revealing healthy, tanned forearms. Through the fog of her brain, Nancy’s first thought was that they must be tourists like her, but they seemed too confident for that, and their shoes were not designed for tramping across miles of an alien city. She caught the soft burr of their spoken German. Their easy sophistication marked them down as bourgeois Berliners, not provincials.

Nancy realised that she was doing the same to everyone she saw; assessing them, deciding who they were, what they might be concealing. Suddenly everyone looked like plainclothes officers. She had an urge to confront everyone in the crowd and demand of each of them, ‘Are you secret police? Are you secret police?’ She pulled her sun hat down over her hair. Her hands were sweaty and her dress clung to her body. She clutched her slim shoulder-bag closer to her side and walked on.

It was late afternoon but the heat of the day had not yet relented. She and Lydia had taken the U-Bahn from the Reichssportfeld station at the Olympic Stadium in the west of the city and had spent two hours shopping and sightseeing in the broad avenues and boulevards around Friedrichstrasse and Unter den Linden. Now she had slipped away and was alone, the map of the streets she must walk down memorised.

The city was full of thousands of tourists, here for the Olympics and all the fun surrounding the games. No one is following you. She said the words under her breath. She gripped her hands into fists, then released, then gripped again. She took deep breaths to calm herself and increased her pace, trying to make herself look businesslike, less foreign. Less interesting.

God, she was a fool, a bloody novice. She had been told what to do, of course, how she must lose possible pursuers with backtracking, circling and stops. How to spot a tail. But that was theory; this was reality.

The man with the sandals had disappeared into the heaving mass of people. Perhaps he had been one of many; perhaps someone else was now on her case. Nancy had attempted to dress as anonymously as she could, in a shapeless green frock, with her hair braided and pinned up around the top of her head. In their shared hotel room, Lydia had looked at her oddly. ‘I know what you’re thinking,’ Nancy had said. ‘You think I look like a bloody little Waltraud.’ Lydia had raised an eyebrow. A Waltraud was their private derisory name for the sort of Nazi girl who belonged to the BDM, wore dirndls and eschewed make-up and cigarettes. Was there anyone in the world less like the clean-living jungmädel ideal than Nancy Hereward? They had both fallen about laughing.

She headed south an

d westwards. On every corner and from every public building, the swastika banners fluttered in the warm breeze, black on a white circle in a sea of red. Every one of them seemed like a personal threat. Turning right into a side street, she stopped at a butcher’s shop window and gazed at the cuts of meat and the endless varieties of sausage without really seeing them. She tensed as an old woman bustled up to her elbow and put a letter in the red Reichspost box fixed to the wall at the side of the shop, then ambled away at snail’s pace. No one was following. She carried on, walking further away from the main arteries of the city. At the end of the street she turned right then, quickly, went left. The area was residential now, a respectable mixture of smart tenement blocks, parks and churches, very different from the regimented grid of streets bordering Friedrichstrasse.

She knew that Lydia would be getting worried. Nancy had told her she would only be gone twenty minutes; she should wait for her at the Victoria with a coffee and cake and her book. ‘I just want a little time on my own,’ she had said. Lydia had shrugged, clearly puzzled, but seemed to accept it. This was going to take a lot longer than twenty minutes; Lydia would just have to wait.

She turned again into the road she had been seeking. Narrow and cobbled with a half-timbered tavern, which must have been old when Otto von Bismarck was young. She looked around once more. The street was almost deserted, save for a boy of about twelve. She stopped three houses to the left of the tavern, outside the front door of a three-storey building. Number six, one of the flats at the top of the house. She pressed the button twice, waited three seconds, then pressed again.

A dormer window opened twenty feet above her and a face peered out. ‘Ja?’

‘Guten tag, Onkel Arnold!’

He hesitated no more than two seconds, then nodded. ‘Einen moment, bitte.’

Half a minute later, the front door opened.

‘Come in,’ he whispered. His English was heavily accented, but precise. He was a balding man in his mid-thirties and he was frightened.

Nancy stepped into the gloom of the hallway. On either side of her there were doors to apartments. In front of her was a staircase. ‘Here?’ she suggested.

‘No, please, not here. Come upstairs.’

As soon as he had closed the door to his flat, she removed her hat and tossed it on the table. Then she opened her bag and took out a brown envelope. She thrust it at him. ‘It’s all in there.’

He slid the papers out and studied them, then gave her a strained smile. It would take a great deal more than this delivery of forged papers to wash away the stresses of his life. ‘Thank you, miss. Truly, I don’t know how to thank you or repay you. You have risked a great deal for me.’

‘Not for you, for the cause.’

‘I thank you all the same. Can I make you a cup of tea? Or coffee perhaps? It is ersatz, I’m afraid.’

‘No, I must go.’ She hesitated. She was shaking. ‘Do you have a lavatory?’

‘Yes, it is shared. Across the landing.’

No, not here. It would be too risky. She had to get to safety. She tried to control her shakes. ‘Forget it. I have to leave now.’

‘I think if you were really my niece you would stay a little while, don’t you? Having walked all this way?’

‘No one saw me coming.’

‘My landlord would have seen and heard you ringing the bell and calling out my name. He sees everything.’

‘I’ll stay ten minutes.’ Nancy took a grip of herself. ‘I am thirsty. Perhaps you have something a little stronger than tea?’

‘Peach schnapps. It is the only alcohol I have, I’m afraid.’

She made a face. ‘Better than nothing.’

They sat together in the man’s sweltering, badly furnished sitting room, the ceiling sloping acutely beneath the eaves. The open window let in only warm, dirty air. Arnold Lindberg was a physics professor from Göttingen, but in this house he was Arnold Schmidt, unemployed librarian. She could smell the sweat of his fear. His pate was glistening and there were beads of perspiration on his brow and on his upper lip. He lit a cigarette and she could see that his fingers were trembling. As an afterthought, he thrust the packet towards her, but she shook her head. ‘A glass of water,’ she said. The sugary-sweet peach schnapps stood on the table in front of her, untouched. Perhaps she could wash it down.

He went to the basin and filled a glass. She drank it quickly, then asked for another.

‘So tell me, miss, what do you think of the new Germany?’

‘You mean the National Socialists?’

‘Who else?’ He gave a hollow laugh. ‘But please, do not name them.’

Don’t say the devil’s name for fear that he might think you are calling him. ‘I loathe them,’ she said. ‘That’s why I’m here.’ At last, she threw back the schnapps. It was not as sweet as she had feared. Not what she really wanted or needed, of course, but that would have to wait.

‘I pray you never learn what it is like to live here like this,’ he said. He began talking of his fugitive life as both a Jew and a communist, spurned by the university where he had been both student and professor. ‘The Deutsche Physik make it impossible. They take our jobs for the crime of our race. In the twenties I worked with the great names – Einstein, Bohr. I counted them as friends, you know. Leo Szilard, too. Such a funny man. So many others – hundreds of us swept away by men without brains. Lise Meitner is still here, still working because she is Austrian. I want only to be with my friends and colleagues again and to continue my studies and teaching. Leo has said he will find me work and accommodation, if only I can get to England.’ He shook his head. ‘But a warrant is out for my arrest. All ports and railway stations have been alerted to stop me leaving. My crime? Insulting Himmler, the bastard. I will not embarrass you by telling you what I said, for I confess it was obscene.’

She already knew what he had said. Something about Himmler being promoted to Reichsführer in return for sucking Hitler’s cock. One of Arnold’s students had denounced him.

Nancy stood up. ‘I have to go,’ she said.

‘Yes, of course. I have kept you too long – but it is safer, you see.’

‘I hope the papers are what you want.’

He nodded. ‘Thank you again. Thank you.’

She picked up her hat and went to the door, pulling it open. She looked down the empty staircase. She was about to go when she turned round. He was standing there, clasping the envelope she had brought him. He looked pathetic. ‘Good luck,’ she said. You’ll need it.

She took a more direct route back, across the Tiergarten towards the Brandenburg Gate. She looked at her wristwatch and saw that she had already been well over an hour. Beneath her frumpy green dress, her body was as slippery as a wet eel.

‘I was about to send out a search party for you,’ Lydia said when Nancy, sweating and hot, finally came round the corner and slumped down on the seat opposite her at the Victoria café. ‘You’re soaked! You look as though you’ve been running.’

Nancy was frantic now, upturning her bag on the table. From the debris, her scrabbling fingers clutched at a silver syringe.

Lydia’s mouth fell open. ‘Not here, Nancy! For pity’s sake, not here in front of all these people!’

Nancy ignored her and with a shaking hand thrust the tip of the eedle into a small vial and filled the syringe. Lydia looked round anxiously; Nancy stretched her left arm out on the white tablecloth. A thin vein bulged from the white flesh on the inside of her elbow. The needle slipped in, a speck of blood seeped out. She pushed in the plunger of the syringe and let out a low moan.

Neither woman saw the boy looking in through the café window.

ENGLAND,

MONDAY NOVEMBER 30, 1936

CHAPTER 2

He drove the little MG two-seater into a large village in south Cambridgeshire. He was hungry and thirsty and the local inn looked inviting, the sort of place he would have visited on a summer’s afternoon in the old days. Rural English. Wholeso

me food and strange beer.

His assessment was accurate. The Old Byre was a traditional coaching inn with rooms, good food, a log fire and a selection of half a dozen ales and beers. He ordered a steak and kidney pie with potatoes and peas and a pint of bitter. He ate the food hungrily, but he barely drank.

‘Is there something wrong with your beer, sir?’

‘It’s fine.’

‘The keg’s new on today. Can I get you something else?’

The waitress was a woman in her late thirties with loose curls, a figure that hadn’t succumbed to gravity, and a wanton eye. There was a warmth to her, enhanced by the glow of woodfire in a broad open hearth. She was flirting with him.

‘I’ve got to stay awake. I still have a long drive ahead of me. Perhaps a coffee?’

‘We don’t do coffee, sir.’

‘Not even in the landlord’s own accommodation?’

‘I could ask him.’

‘That would be kind of you.’ He flashed his best Hollywood smile. ‘Black, no sugar, please.’

A few minutes later she reappeared with a cup of coffee. As he took it, she said, ‘Beg pardon, sir, might I ask if you are travelling far this evening?’

Had she blushed as she spoke? No, far too brazen for that. It was merely the heat of the fire that brought colour to her cheeks. ‘A little way yet,’ he said. ‘Thank you for the coffee. I am sure it will do me very well.’

‘Have you really got to drive on, sir? They say there’ll be a fog. It’s very late and we have some comfortable rooms to rent. Not many travellers at this time of year, you see. I’m sure if I had a word with the landlord, he’d do you a favourable rate.’

She had touched his hand, deliberately, as she handed him the cup. His initial suspicion was correct. If he stayed, she would come to his room. One of that lost generation blighted by the war, perhaps she took her pleasures where she could among the travelling salesmen who stayed here. On another night he might well have obliged, but he could not stay, and anyway he did not want to leave too large a footprint. As the shutters came down, he paid the bill, took his leave of her, and drove on into the night.

A Prince and a Spy

A Prince and a Spy Traitor js-4

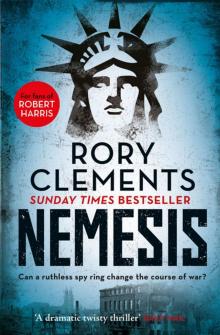

Traitor js-4 Nemesis

Nemesis The Heretics js-5

The Heretics js-5 Corpus

Corpus The Heretics (John Shakespeare 5)

The Heretics (John Shakespeare 5) Nucleus

Nucleus Traitor

Traitor Prince - John Shakespeare 03 -

Prince - John Shakespeare 03 - The Heretics

The Heretics Martyr js-1

Martyr js-1 Revenger

Revenger Prince js-3

Prince js-3 John Shakespeare 07 - Holy Spy

John Shakespeare 07 - Holy Spy The Man in the Snow (Ebook)

The Man in the Snow (Ebook)